By no means is all my work carried out in well-known or particularly important buildings. Some of the more interesting projects take place in houses of a much smaller scale. This was certainly the case here.

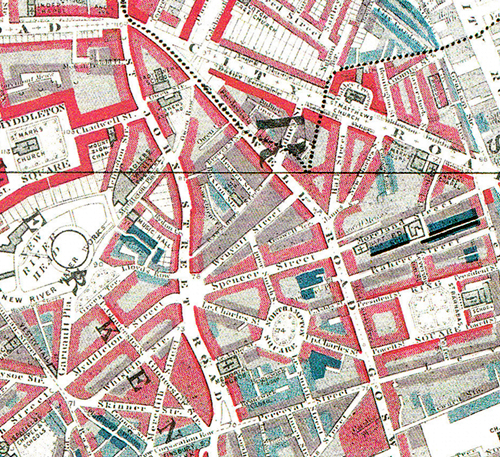

The subject of this investigation is a terraced house of yellow and brown brick set in Flemish bond. It is of three storeys over a basement with two windows on the first floor and one on the second floor. The roof is obscured by a parapet. The house has a round-arched entrance with pilaster jambs and fanlight and a panelled door of original design. The area has railings with spearhead finials that appear to be original. The terrace itself is believed to date from 1798-1800.

A brief search on the Internet for information on previous occupants of the house came up with the following information:

1) In 1807 the house might have been owned by James Winns, a bricklayer.

2) In 1822 the house appears to have been occupied by William Poole a goldsmith.

3) In 1840 William Thomas, a clock-maker, is mentioned as having lived there.

4) Francis Nisbet, a silversmith, was living there in 1856.

5) In about 1870, Henry Slater, a planemaker is recorded as working in the house.

It is no surprise to see such a list of artisans occupying a house in this area. This was common practice as suggested in a recent study of the neighbourhood:

“In London manufacturing often took place either in small workshops located in the backyards of houses or in one or two rooms in the houses themselves. This was particularly true of the watchmaking trade which was characterised by small employers and individual workers often working on their own account. Wherever handicraft work was more important than mechanisation, and where the division of labour allowed production to be broken down into separate components, domestic industry was important. As a result, although street maps might suggest that an area was residential – by virtue of the absence of factories – the truth was that for many home and work were one and the same.”1

Charles Booth’s Poverty Map of 1889 indicates that the street in which the house stood was –

Mixed. Some comfortable, others poor

The Panelling

I was asked to take samples of paint from the panelling in the rear room on the ground floor.

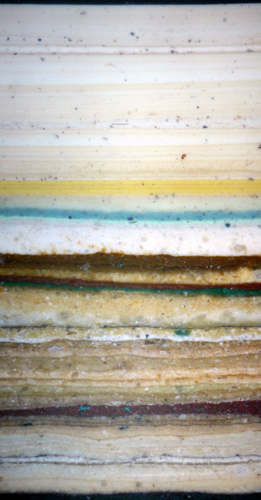

When examined, the sequence of paints on the west wall of the rear room is remarkable, not for the colours or treatment, but for the sheer number of decorative schemes. A total of approximately 52 schemes were applied.

The timber was initially primed with a coat of red oxide pigment in oil. An undercoat consisting of lead white and chalk was next used and this was followed by a coat of a similar mix tinted with yellow and red iron oxides plus black, which produced an olive-brown colour. A coat of glaze can be seen next. The effect would have been of a dark, shiny finish.

The second scheme saw a dramatic change in colour – an off-white undercoat composed of lead white with a proportion of chalk was employed and this was followed by a coat of lead white ground in oil and tinted with tiny amounts of iron oxides. A thin layer of oil glaze was then applied to complete the sequence. The overall effect would have been a shiny pale stone colour.

The third scheme was a grey that would have been known as Lead Colour, and was tinted with particles of carbon black. This was also glazed.

The same type of early paints were found in the house (built in 1730) and occupied by Benjamin Franklin from 1757. There are also similarities to early paint layers recently examined at Queen Anne’s Gate, of 1705, and the house occupied by the composer George Frideric Handel between 1723-1759.

The strong impression when examining these early layers was that they had been taken from early eighteenth century panelling. However, the listing suggests that the house dates from the final years of that century. Is it possible that the panelling was reused from elsewhere, or that the house is older than believed?

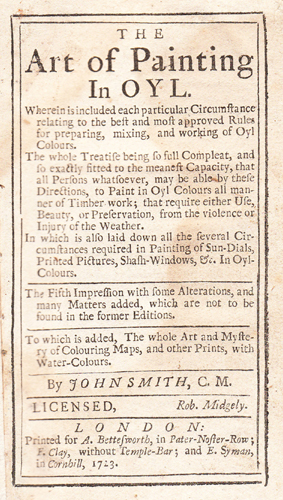

It was interesting to see how the first few schemes of paint on the panelling were given a thin coat of oil glaze in order to provide a semi-gloss finish. In spite of modern notions of eighteenth century practice, such a finish was considered highly desirable, as can be seen in the following quote of 1723:

“Take notice also, That all simple Colours used in House

Painting, appear much more beautiful and lustrous, when they

appear as if glazed over with a Varnish to which both the drying

Oyl before-mentioned contributes very much, and also the Oyl of

Turpentine, that the Painters use to help to make their Colours dry soon…”2

The dark red-brown primer is also something that one tends to see on joinery of the early 18th century. The red iron oxide:

“’tis of great use among Painters, being generally used as the first and priming Colour, that they lay on upon any kind of timber work, being cheap and plentiful, and a Colour that works well, if it be ground fine, as you may do with less labour than some better Colours do require”

To date, I have only ever found the use of red/brown primer and glazed finishes on panelling of the early eighteenth century.

Repainting Cycle

Over the years I have taken samples from many early painted surfaces. One can learn much from the frequency of decoration and very often clues can be given to the dating of alterations that might have taken place. At the same time the number of layers found is likely to indicate whether any schemes have been stripped or elements replaced.

When one divides the age of the building by the number of schemes found one will obtain what is known as the repainting cycle. For example the average repainting cycle of similar rooms in four buildings erected between 1705 and 1730, and examined recently, varied between 7 and 10 years.

However, when these figures are applied to the paint layers found in this house I was faced with a puzzle. For example, if the age of the building is taken away from the approximate date of the last decoration (1798 – 2005) one is left with a figure of 207. If this is divided by the number of schemes (52) there is a suggestion that the panelling was repainted every four years, which is nearly twice as frequent as the examples given above.

There again, if one applies a repainting cycle of five years the first scheme would be likely to date from about 1750. A six year cycle would give a date of fifty years earlier. The nature of the early schemes perhaps suggests a date of the first quarter of the eighteenth century. However, it would mean that either the date of construction is incorrect or that the panelling had been reused. Further sampling would be necessary to see which was the case.

Needless to say neither the client nor I were expecting this. It is not enough for the paint analyst to just report that the first scheme was “brown”. Every finding should be tested by the question “So What?” – “What does this mean?”. Paint analysis, when used properly, can provide answers to many questions. It can also pose questions when none were expected.

1 Finsbury: Past, Present & FutureReport for EC1 New Deal for Communities compiled by Dr David R Green, King’s College London, May 2009.

2John Smith. The Art of Painting in Oyl. 5th edn.1723.

Postscript – Although not asked to, I took the opportunity to sample the railings while I was on site (I always do, in order to build up a clearer picture of their treatment). Once again they conformed to what I now regard as ‘the norm’.

View Larger Map

Hi Patrick – I’m just coming to the end of a project in Russell Square (the intial construction was completed in 1806) where there appears to be a chalky orange primer evident on some sections of the original joinery – generally, how useful is the primer in dating?

Michael

Thanks for that Michael. I often find that the primer provides more information than the finish coat. It’s a very useful aid to dating and helps with the comparison of samples.