A previous post has already introduced the subject of a most useful work that was published in the 1930s – Parsons’ Decorative Finishes. Subsequently I have used it as a ‘prompt’ for posts dealing with Water Paint, Flat Finishes; Gloss Enamel Finishes and several other types of paint.

The book is divided into 17 sections and one of these (Section Ten) will be considered in this post which looks at the Cellulose Lacquer and Cellulose Wood Finish offered by Thomas Parsons’ at the time.

Cellulose Lacquer

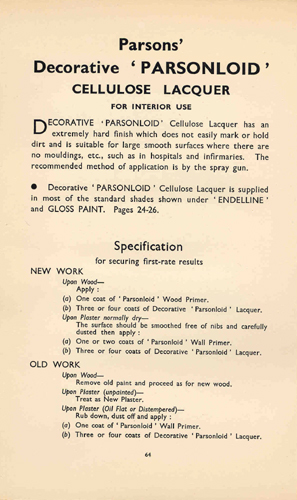

Parsons’ Parsonloid Cellulose Lacquer had an extremely hard finish which did not easily mark or hold dirt and was suitable for large smooth surfaces where there were no mouldings, for example in hospitals and infirmaries. It was recommended that it be applied by spray gun.

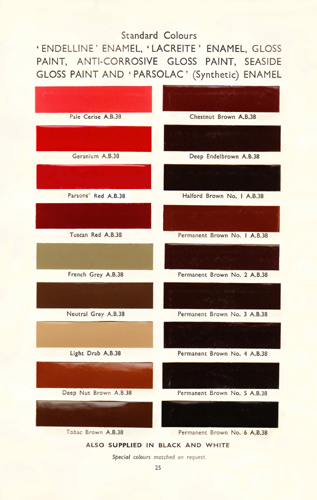

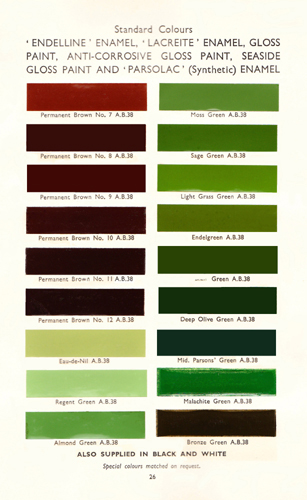

It was supplied in most of the standard shades shown under ‘Endelline’ and ‘Gloss Paint’, the colour cards for which are shown on this page.

Specification for securing first-rate results

NEW WORK

Upon Wood –

Apply:

a) One coat of ‘Parsonloid’ Wood Primer.

b) Three or four coats of Decorative ‘Parsonloid’ Lacquer.

Upon Plaster normally dry –

The surface should be smoothed free of nibs and carefully dusted then apply:

a) One or two coats of ‘Parsonloid’ Wall Primer.

b) Three or four coats of Decorative ‘Parsonloid’ Lacquer.

OLD WORK

Upon Wood -

Remove old paint and proceed as for new wood.

Upon Plaster (unpainted)

Treat as New Plaster.

Upon Plaster (oil Flat or Distempered) –

Rub down, dust off and apply:

a) One coat of ‘Parsonloid’ Wall Primer.

b) Three or four coats of Decorative ‘Parsonloid’ Lacquer.

There is no doubt that cellulose finishes were more costly than those with which the decorator had been familiar, but they did offer important advantages; for example, speed, the finish being harder and more durable within a short time of application than anything obtainable with oil-paint or varnish. As a result cellulose did not absorb dirt as readily as the more traditional finishes and was cleaned more easily. Anything from a full gloss to a dead flat finish was achievable.

Cellulose was also very amenable to polishing. For exterior work, such as doors, it was preferable to employ an eggshell finish that could be polished to a high gloss.

Cellulose Wood Finish

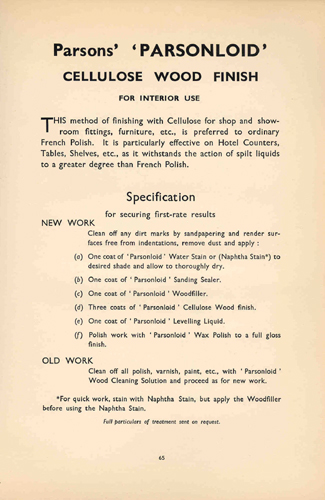

Parsons’ Parsonloid Cellulose Wood Finish was said to be better for finishing shop and showroom fittings and furniture than French Polish. It was also more effective on hotel counters, tables, shelves etc., as it better withstood the action of spilt liquids.

Specification for securing first-rate results

NEW WORK

Clean off any dirt marks by sandpapering and render surfaces free from indentations, remove dust and apply:

a) One coat of ‘Parsonloid’ Water Stain or (Naphtha Stain*) to desired shade and allow to thoroughly dry.

b) One coat of ‘Parsonloid’ Sanding Sealer.

c) One coat of ‘Parsonloid’ Woodfiller.

d) Three coats of ‘Parsonloid’ Cellulose Wood Finish.

e) One coat of ‘Parsonloid’ Levelling Liquid.

f) Polish work with ‘Parsonloid’ Wax Polish to a full gloss finish.

OLD WORK

Clean off all polish, varnish, paint, etc., with ‘Parsonloid’ Wood Cleaning Solution and proceed as for new work.

* For quick work, stain with Naphtha Stain, but apply the Woodfiller before using the Naphtha Stain.

A work published in 1930 tells us that cellulose wood finishes were offered in a variety of grades, including the very popular semi-gloss type and a full gloss variety – the latter being of a quality “fit to tax the skill of the finest French polisher.” It was accepted that their application required considerable practice and experience, but it was agreed that they were easier to use than French polish. It was pointed out that it was essential to use all materials, stains, wood fillers, thinners, etc., specified by the maker.1

History of Nitrocellulose Coatings

I will be honest – I have seldom encountered nitrocellulose coatings from the 1930s other than as sprayed lacquers on joinery on projects such as Eltham Palace and BBC Broadcasting House. For this reason I had delayed looking at this section of the Thomas Parsons’ book. However, recently I have been asked to review a new book by Dr Harriet Standeven entitled House Paints, 1900-1960 and published by the Getty Conservation Institute. There really isn’t anything like this work in print and she deals with the subject in an excellent fashion.

The following owes a great debt to Dr Standeven’s book. We are told that the:

“…real impetus for the development of nitrocellulose coatings came in 1918, at the end of World War I. Numerous manufacturers found themselves with huge stockpiles of raw materials and plants capable of large-scale explosive manufacture but no market for their product in peacetime. This prompted companies to put their products to other uses, and coatings provided a promising alternative market. In the United Kingdom the Nobel Explosives Company2 devised a method of pigmenting airplane dope with the relatively new pigment, antimony oxide, and around 1919 introduced the first interior enamel based on nitrocellulose, Glossy White S.2567; it reportedly surprised DuPont’s chemists as late as 1925 with its outstanding qualities. And in 1920 the U.K. company Frederick Crane introduced its range of Cranco nitrocellulose enamels.”3

Their potential was understood by the car industry who developed the product further and made it even more attractive to the decorative coatings industry, and by the mid-1920s a number of firms were producing nitrocellulose brushing lacquers for use on metal, wooden trim and furniture. However, their use was short-lived in the domestic market as other quick-drying products that were easier to handle and containing tung oil, ester gum or phenolic resins were introduced. On some occasions the brand name was retained in spite of major reformulation.

Minutes after application most of the solvent had evaporated leaving the surface of the film tacky. However, as the nitrocellulose remained wholly or partially soluble in the carrier solvent any attempt to ‘touch up’ or apply a second coat would result in a mess. In time, the better grades contained a larger proportion of solids, in the form of gums and resins, and also of nitrocellulose. High grade solvents and diluents were added and the price was usually an indication of the quality.

The brushing cellulose lacquers were initially popular with the houseowner for the decoration of small household items, especially in the United States. The rapid drying nature backed by big advertising campaigns proved a great attraction.

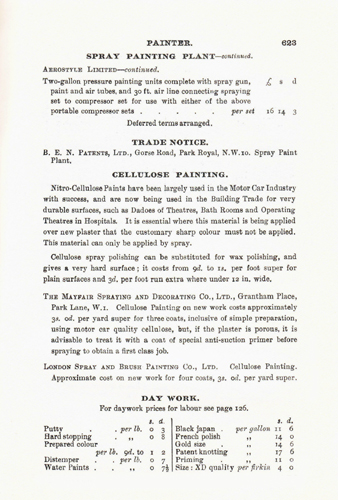

The professional painter, on the other hand may have flirted with the product, but it never took off. However, for someone prepared to invest money in the equipment and time in learning the technique, spraying cellulose lacquers offered many advantages, especially to those with a workshop. Thomas Parsons’ Parsonloid was one such product.

A work published at the same time as Parsons’ Decorative Finishes suggests that:

“For general use the spray plant is indispensable, except where the brush may be used as mentioned. A portable plant for use with electricity or internal combustion engine, the compressor being remote from the scene of operations, is now standardized by most spray-plant manufacturers, who also supply portable fans to work in the doorway or open window where the spraying is carried out, thus providing for the safety of the operators. Such equipment is inexpensive in use and very handy, and where the work is fairly extensive it will be found thoroughly economical.”4

Dr Standeven tells us that the first residence claimed to have been entirely decorated using this technique was in the spring of 1927 -

“…on a new house situated at Grange-over-Sands, overlooking Morecambe Bay. The walls first received a coat of water paint, then a spray application of nitrocellulose. Each room took no more than twenty minutes to paint and could be recoated in just ten: the speed of application convinced the decorators, Messrs J.M. Smith and Son, of Liverpool, that all home owners would soon be demnanding these types of finishes.”5

As we know, this never happened.

Current Availability of Colours

As with almost all the colours shown on this site the colours shown here could be mixed into conventional modern paint by Papers and Paints Ltd

Notes

1 Jenson & Nicholson Ltd. Paint and its Part in Architecture. 1930. 229.

2 Later to became part of ICI, the manufacturers of Dulux paints.

3 Harriet Standeven.House Paints 1900-1960. The Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles. 2011. 55.

4 (Jenson & Nicholson Ltd. 1930, 230).

5 (Standeven 2011, 61).

View Larger Map

[...] http://wood-finishes.decor-works.co.uk/wood-lathes/ http://patrickbaty.co.uk/2011/11/01/parsons-decorative-finishes-15-parsonloid-cellulose-lacquer/ http://wood-finishes.decor-works.co.uk/living-word-church-carmarthen/ [...]

[...] http://patrickbaty.co.uk/2011/11/01/parsons-decorative-finishes-15-parsonloid-cellulose-lacquer/ http://wood-finishes.decor-works.co.uk/linseed-oil-on-rusted-metal/ [...]