Swakeleys House is a Grade I listed seventeenth century mansion in Ickenham, in the London Borough of Hillingdon. It was built in 1638 for the future Lord Mayor of London, Sir Edmund Wright.

Swakeleys was built to impress, in an exuberant style of architecture later dubbed ‘Artisan Mannerism’ by the historian Sir John Summerson. The style was developed by London craftsmen for patrons who were keen to update the prevailing Jacobean style with classical elements taken from Italian and North European architecture. This is shown on the exterior, where traditional Tudor-style windows are combined with up-to-date Dutch gables. This particular kind of ‘Dutch gable’ is, in fact, peculiar to English architecture and has been called the ‘Holborn gable’, after the London district where they first appeared

The Estate was inherited by Sir Edmund Wright’s daughter, Katherine. Katherine’s husband, Sir James Harington, was a prominent Parliamentarian, fighting against the monarchy. England by this time was deep in Civil War. It was Sir James Harington who installed the arched screen in the Great Hall. When the monarchy was restored in 1660, Sir James fled the country to save his life, leaving his wife alone. Katherine sold the Estate to the rich banker and Royalist financier, Sir Robert Vyner.

When Sir Robert Vyner acquired the Estate in 1665 he was fast becoming one of the richest men in the country. In that year he invited the diarist Samuel Pepys to dinner, whose description is an evocative document of Swakeleys at that time:

‘Merrily to Swakeleys, Sir R. Viner’s. A very pleasant place, bought by him of Sir James Harington’s lady. He took us up and down with great respect, and showed us all his house and grounds; and it is a place not very modern in the garden nor house, but the most uniform in all that ever I saw; and some things to excess. Pretty to see over the screen of the hall (put up by Sir J. Harington, a Long Parliament man) the King’s head, and my Lord of Essex on one side, and Fairfax on the other; and upon the other side of the screen, the parson of the parish, and the lord of the manor and his sisters. The window-cases, door-cases, and chimneys of all the house are marble.. and after dinner Sir Robert led us up to his long gallery, very fine, above stairs (and better, or such, furniture I never did see), and there Mrs. Worship did give us three or four very good songs, and sings very neatly, to my great delight.’1

This account by Samuel Pepys illustrates how Swakeleys was used as a place of entertainment and for the cultivation of power and influence. Pepys’ remark that it was ‘not very modern’ shows how quickly architectural style was moving. Vyner did not modernise the house extensively, most of his money being spent on loans to the King and his government, which gave him immense political power.

By 1750 Swakeleys was in the hands of the Rev. Thomas Clarke, in whose family it remained until 1923. Members of the family had their coats of arms painted onto the Harrington screen. At one time Swakeleys was home to the Foreign & Commonwealth Office Sports Association. Large sections of the grounds were sold off in 1922 and developed as suburban housing. In the 1980s the house was extensively restored and it has been recently tidied up. I advised on the decoration.

Exterior

The elevations are symmetrically designed and of red brick laid in English bond. A regular series of quoins, stone below and render above, can be found on all salient angles. There is a moulded plinth course at ground floor level, and continuous entablatures in render surround the building, including the bay windows at the floor levels. Pediments surmount the entablatures over the windows (except the bays), being triangular in the lower series, and segmental in the upper series. Many of them have strapwork ornament in their tympana. Above the parapet is a succession of brick gables, with plaster scrolls terminating their hollow-shaped sides, which carry entablatures with small pediments in the centre. The windows within the gables have rendered frames, cornice and pedimental heads.

The windows, including the faces of the bay windows, are mostly four lights in width, and are divided by a transoms, making eight lights of equal size. There is one light on each cant of the bays, and one on the return which is in most cases bricked up and rendered. The windows of the hall and dining-room are of black marble which has weathered to grey, these being no doubt the ones referred to by Pepys.

The West elevation (see above) has a central porch and two-storey bay-windows at each end. The main door has a round outer archway of grey marble flanked by Doric pilasters. These support an entablature and broken segmental pediment containing a pedestal carrying an enriched cartouche with helm and mantling.

The upper storey of the two-storeyed porch is now finished with a wooden modillion cornice of apparently 18th-century date. In the centre of the parapet behind the porch the brickwork is taken up to provide a door on to the roof of the porch, flanked by rendered panels, over which is a niche with shell head and scroll sides, containing a man’s bust in Roman costume. A rainwater head on this front has the initials and date E.W. (for Sir Edmund Wright) 1638.

The East elevation is generally similar to the West front but has no porch; in place of this is a grey marble doorway with a segmental keyed head, flanked by later fluted Corinthian pilasters with an entablature. The lower windows in the central bay have cornices and broken pediments. The side windows above have rendered aprons of ornamental strap-work in low relief and between them is an oval window; the central feature of the attic-storey is similar to that on the West front but the niche is empty. The windows may have been arranged to suit the original staircase. It is possible the stair was designed with two lower flights leading to a landing over the door, from which one middle flight would lead to the first floor.

The South elevation shows two large gables over the double central section of the house, and a smaller one over each end. The four windows in the centre are each of six lights in width. The ground-floor windows in the wings have been replaced by tall eighteenth century sashes that reach to the ground, within a frame composed of fluted pilasters and enriched entablature all in stucco. The chimney stacks on this front are of the same date. In the centre is one of a number of finely cast lead rainwater heads which bear Sir Edmund Wright’s initials and the date 1638.

The North elevation is generally similar to the South one but the lower part has later outbuildings erected against it, and the windows in the wings are blocked. The central door with frame is original and has a two-light window in its upper part to light the passage. On each side is a pair of two-light windows, the one on the right giving light to the service stair.

It is not clear how the central feature on the first floor was originally designed as there is now an eighteenth century window with a wrought iron balcony. Above it is an old two-light window, with a pair of small elliptical lights, one on either side. The chimneys on this front have their flues set diagonally on lofty square bases.

The Stables form three sides of a quadrangle immediately North of the house. They are partly of one storey and partly have attics above; the walls are of brick. They seem to have been built at two periods in the seventeenth century but have been much altered. The stables have round-headed doorways and windows, with solid frames. The coach-houses, flanking the entrance, were formerly open to the courtyard on the ground floor and have oak posts with moulded capitals and curved brackets under the moulded bressumer. The roofs are partly original.

Interior

(The key rooms only will be described). The house is entered from the West front leading into the ‘screens passage’. This is a traditional feature originating in medieval houses. The screen itself dates from between 1643 and 1660 and is of wood. It is of three bays divided by Doric columns and flanked by pilasters, supporting an entablature with minor enrichments and a central broken segmental pediment with a bust of Charles I flanked by two crouching lions; the middle bay has a round arch with a keystone and cherub-heads in the spandrels; the side doorways are also round-headed and above each is a cartouche-of-arms supported by cherubs. The North face of the screen is similar but has pilasters in place of columns and a bust of Fairfax

The Great Hall itself is lined with eighteenth century panelling with a heavy dentil cornice at ceiling level. The cornice breaks round two pilasters flanking a central panel over the fireplace, and each window has a pair of fluted pilasters with carved Corinthian capitals. The door architraves, the panels over the doors themselves and the fireplace have bolection mouldings, and the doors, which are of oak and of six panels, retain their old brass hinges and rim-locks. The chimneypiece is of the same period. In it is an iron fireback with the motto non auro sed armis [Not with gold but arms] the initials N.L. and a representation of the fall of Namur and the date 1695.2 The floor is paved with stone with small black squares at the angles. In common with the Dining Room the mullions of the windows are of black marble which is most unusual. In the South window are two roundels executed by Miss Jessie M. Jacob,3 one having the Herbert arms and the other an inscription commemorating the Hon. Mervyn Herbert to whom the connection between the Foreign Office Sports Association and Swakeleys was due. The North wall of the screens passage is lined to half its height with panelling finished with a cornice; the passage to the East has similar panelling.

The present staircase appears to be the third one to occupy this position, although there is no definite indication, beyond the fenestration of the East wall, to show the arrangement of the original stair.

Above the dado of the staircase the walls are painted up to the level of the first floor with rusticated masonry; above this are painted figure-subjects as follows:

On the South wall is the death of Dido. The queen with a wound in her left side is shown supported on a pyre by another woman and in the foreground are two amorini with a lighted torch, and four subordinate figures. A curtain is draped above the scene and over the doorway in this wall is an urn backed by drapery. The ceiling is painted to represent the sky with a winged female figure, probably Juno, seated on a rainbow, on which lean three winged amorini, one of whom holds a peacock. Another female figure is shown seated on the clouds. This extends from the first floor to the ceiling and is represented in an architectural setting with flanking Corinthian columns.

On the North wall (see photograph) is the founding of the city of Lavinium by Aeneas who appears helmeted and in Roman costume. Behind him is a turbaned figure standing in trepidation before a group of four men, one of whom holds in his hand the plans of the city, which is shown as a pentagon with circular bastions at the angles. Above is the figure of Mercury and in the background are buildings. Over the adjoining doorway is painted a large urn on a pedestal with pyramids in the distance.

On the West wall a landscape with a bridge and stream with an architectural setting and a draped curtain; above the adjoining doorway is a small boy with a bow, seated on a pedestal.

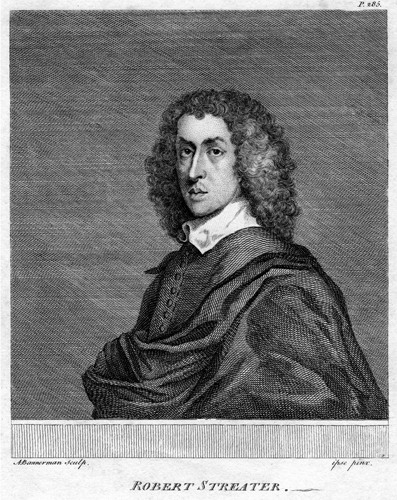

The paintings are attributed to Robert Streater, who was Serjeant-Painter to Charles II. Streater painted the walls of Thomas Povey’s house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and he decorated the Sheldonian Theatre at Oxford. Povey was well known to Sir Robert Vyner, and Streater was admired by both John Evelyn and Pepys.

The great chamber or salon, on the first floor, is 42 ft. by 23 ft. and is 16 ft. high. The walls are now lined with late seventeenth or early eighteenth century panelling similar to that in the Great Hall. The two fireplaces have moulded surrounds of dark grey marble.

The most striking feature of this room is its magnificent plaster ceiling. It is divided into fifteen compartments (with an additional panel over the porch recess), by heavily moulded plastered beams. The mouldings are enriched with classic ornament and the soffits with a double band of guilloche pattern with large rosettes at the intersections of the beams. Except those following the chimney projections, the compartments are rectangular, while to the central compartment the beams are carried round to form an inner circular panel. Sunk elliptical panels are formed in the soffits of the alternate compartments bordering the side walls; the two middle compartments against the end walls have sunk octagonal soffits with a cherub’s head in each spandrel, and the two compartments flanking the middle panel are enriched with laurel wreaths of bold projection. The ceiling over the projecting bay also has a central wreath and in each corner is the head of a cherub blowing. The whole ceiling is surrounded by a heavily moulded cornice with the mouldings enriched similarly to the beams. Although it has been suggested that the purely classical treatment of this ceiling indicates a later date than that of the building of Swakeleys, the ceiling of the chief room at Cromwell House, Highgate, which was building in the same year, has an unmistakable resemblance to the one here.4 The double guilloche ornament of the main ribs is identical, and in both ceilings the circular band of ornament cuts into the square in the same way. It seems highly likely that the ceiling dates to Sir Edmund Wright.

NOTES

From a variety of sources especially the Survey of London Monograph 13, Swakeleys, Ickenham. Originally published by Guild & School of Handicraft, London, 1933.

1 Pepys Diary 8th September 1665.

2 An identical fire-back can be seen on the Rotterdam Museum website.

3 Other work by her can be seen at Southover Church, Lewes and the Malvern College Mission (now the Mayflower Family Centre) in Canning Town, London.

4 A very interesting account of these ceilings can be found on Dr Claire Gapper’s website.

No comments yet. Be the first!