Holborn Viaduct (Farringdon Street Bidge) is a bridge in London and the name of the street which crosses it (which forms part of the A40 road). It links Holborn, via Holborn Circus, with Newgate Street in the City of London, passing over Farringdon Street and the subterranean River Fleet.

It was built between 1863 and 1869, at a cost of over £2 million, and was the first flyover in central London. It spanned the steep-sided Holborn Hill and the River Fleet valley at a length of 1,400 ft, and 80 ft wide.

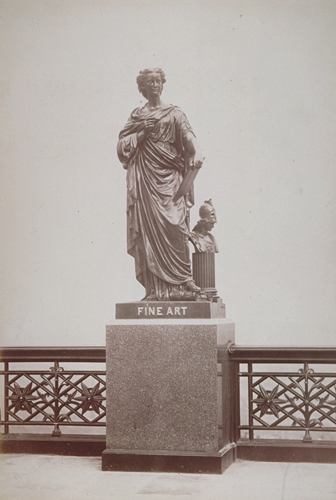

Four statues on the parapets represent Commerce and Agriculture on the south side, both by sculptor Henry Bursill, and Science and Fine Art on the north side, by the sculpture firm Farmer & Brindley. Staircases provide pedestrian access from the bridge to Farringdon Street below.

Brief History

The Holborn Valley Improvements, carried out under the auspices of William Haywood, were the City’s showpiece contribution to the Victorian modernisation of the capital, a sort of counterpoint to the Bazalgette scheme.1 The aim was to provide easy access to the City at its north-west corner, and to create a ‘slip-road’ to the new food markets at Smithfield. Above all the improvements were intended to remedy ‘the evils resulting from the declivities of Holborn Hill and Skinner Street’, the streets taking traffic into and out of Fleet Ditch. Negotiating these slopes, according to the Architect, involved all traffic entering the City in ‘enduring much of the danger and delay which lay in the way of an enemy when London was a walled town.’ This was a project which had long concerned the City Architect, J.B. Bunning, whose first proposals had been presented as far back as 1848. Indeed he had been actively pursuing the matter shortly before his death on 7 November 1863. It was during the ‘interregnum’ between Bunning’s death and the appointment of his successor, Horace Jones, that the Improvement Committee advertised for designs and estimates for raising Holborn Valley. Eighty-four individuals responded, sending in 105 designs, illustrated by 206 drawings and 13 models.

Following the committee’s report on the Court of Common Council, presented on 6 November 1863, the insider, William Haywood was chosen for the task. Premiums were presented to the runners-up, R. Bell and T.C. Sorby. A Bill for the improvements was presented in Parliament, which was passed into an Act on 23 June 1864, and on 29 June, the Court of Common Council referred it to the committee for execution. A further Holborn Valley Improvement Act, for additional work, was passed in 1867. The contract for the building work was taken out with Messrs Hill and Keddell on 7 May 1866, and on 3 June 1867 the foundation stone of the Viaduct was laid. On 6 November 1869 Queen Victoria opened both the new Blackfriars Bridge and Holborn Viaduct, a major civic event, involving a great deal of temporary architecture and sculpture.

When Her Majesty reached the platform and the carriage halted, the Lord Mayor presented Mr. Deputy Fry and Mr. Haywood, the engineer of the viaduct. Mr. Fry then handed to the Queen a volume elaborately bound in cream-coloured morocco, relieved with gold, and ornamented with the Royal arms of England, in mosaic of leather and gold; and Her Majesty declared the viaduct open for public traffic.3

Watercolour presented to Queen Victoria © London Metropolitan Archives – CLC/295/MS03496

NB The original scheme was different to that shown here

The two northern step-buildings of Holborn Viaduct were severely damaged in war-time bombing, and what was left of them was demolished. In 2000 Atlantic House, at the north-western corner of the Viaduct was taken down, and Haywoods step-building on this corner was reconstructed, complete with copies of the original Victorian statuary by The Carving Workshop, Cambridge.4

Watercolour presented to Queen Victoria © London Metropolitan Archives – CLC/295/MS03496

NB The original scheme was different to that shown here

Paint Analysis

I was commissioned to establish the decorative history of the viaduct.

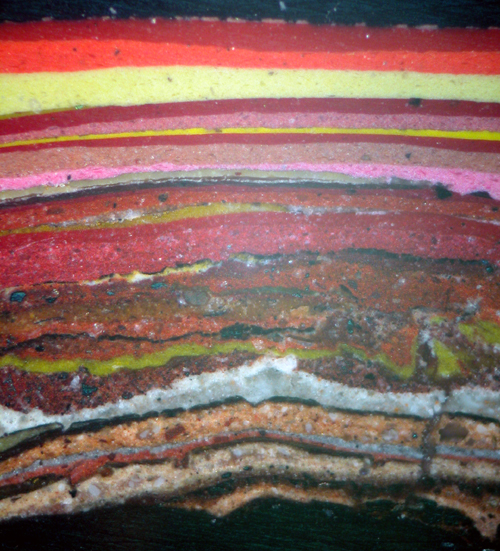

The bridge appears to have been painted on at least fourteen occasions. Few of the samples displayed an uninterrupted sequence of coatings and a close comparison of all of them was necessary to unravel the history.

An examination of the samples taken showed evidence of polychromy on the first two occasions that the bridge was painted. The lamp standards were painted dark green with red-brown details at the base and gilded; the balustrade itself was a browner colour (possibly chocolate brown) and gilded and the City Arms were painted chocolate brown and gilded.

© London Metropolitan Archives – Record: 25660

From the 1880s until the 1930s however the viaduct was painted in a different way, with a deep red iron oxide applied to all elements and gilding employed to varying degrees.

City Arms

At first I was surprised to see that the Coat of Arms of the City of London was painted either chocolate brown or red iron oxide and gilded. However, then I remembered from the work that I had undertaken on Tower Bridge that the Arms were only officially confirmed at the College of Arms on 30th April 1957. At that time the blazon was formalised as:

Arms: Argent a cross gules, in the first quarter a sword in pale point upwards of the last.

Crest: On a wreath argent and gules a dragon’s sinister wing argent charged on the underside with a cross throughout gules.

Supporters: On either side a dragon argent charged on the undersides of the wings with a cross throughout gules.

A previous post on Heraldic Colours (or Tinctures) explains most of these terms.

On all subsequent occasions the viaduct continued to be painted a red iron oxide colour and gilded, but the Arms were painted in their correct heraldic manner. The viaduct is currently being painted in this way.

Clearly not everyone was impressed by the design of the Viaduct, as W.B Yeats recounted:

“When I had just published my first book, I met William Morris in Holborn Viaduct, and he began to praise it with the words, ‘This is my kind of poetry’, and promised to write about it, and would have said I do not know how much more if he had not suddenly caught sight of one of those decorated lamp posts, and waving his umbrella at the post, raged at the Corporation.”5

This horrifying photograph shows just how difficult it can be to find original paint from structures that have received this sort of treatment:

Sources and Notes

1 The development of the Thames Embankment.

2 Philip Ward-Jackson. Public Sculpture of the City of London. Liverpool University Press. 2003. 204-214.

3 This is the volume now in the London Metropolitan Archives and which contains the two watercolours illustrated here.

4 (Ward-Jackson 2003, 206).

5 The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats vol III: The Irish Dramatic Movement. 195-96. Simon and Schuster. 2008. I am most grateful to Gary Kemp for drawing this to my attention.

Credit

I am most grateful to the London Metropolitan Archives for their help in my research and for their generous permission to use a number of images in their collection.

I am also indebted to Philip Ward-Jackson’s excellent book on Public Sculpture of the City of London, which has been plundered extensively.

View Larger Map

[...] explaining how the bridge has been through a number of paint jobs in its life – 14 according to paintwork analysis – in varying levels of gaudiness. “When it was opened in 1869, it was painted with a riot [...]