The house was built in 1674 by the third Earl of Lindsey on the riverside site of Saint Thomas More’s garden and is thought to be the oldest house in Kensington and Chelsea. It was extensively remodelled in 1750 by the German aristocrat Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf, head of the Moravian Church who intended to make it the centrepiece of a religious settlement.

Ten years after the death of Zinzendorf the house was divided into seven dwellings: five in the main range and one smaller house in each of the two-storey wings at the ends. The terrace of seven houses thus created was renamed Lindsey Row. Today, it is known as Nos. 96 to 101 Cheyne Walk.

Previous residents have included the engineer Marc Brunel who lived in the middle section of the house (now No. 98) in the first decade of the nineteenth century and his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel who grew up there. Another early resident (of No. 96) was the collector H.C. Jennings (‘Dog Jennings’), who lived there in the early 1800s, where he created a small museum.

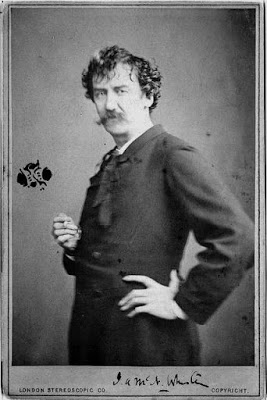

The Romantic painter John Martin, lived in one of the outbuildings at No. 98 from 1849–1853 and in 1863 the American-born painter, James McNeill Whistler moved into No. 101. By 1867 he had set up house at No.96. It was here that he lived longer than anywhere else (until 25th June 1878) and enjoyed the most productive and significant decade of his career.

It was at No. 96 that Whistler painted his a series of experimental ‘Nocturnes’ and ‘Arrangements’ as well as his great portraits. It was here also that he gave his Sunday breakfasts. Following his house-warming party on February 5th 1867, when the two Rossettis1 dined with him, William Michael Rossetti said that

“There are some fine old fixtures, such as doors, fireplaces, and Whistler has got up the rooms with many delightful Japanesisms.”

The door to the right hand side leads to the Entrance Hall

During his time there Whistler became known as a designer of fashionable interiors, with a particular talent for creating unified colour schemes for the display of art. Giles Walkley2 summarises Whistler’s decorating style as

“vivid accents [on] expanses of unpatterned pastel tints, delimiting the latter with substantial contrasting margins”.

Contemporary accounts refer to pinkish yellow walls and white woodwork in the drawing room, a scheme of light and dark blues in the dining room, a studio with grey walls and black borders, and “a gloomy staircase brightened up by lemon yellow walls above a golden dado dotted with butterflies.”

(Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

The American journalist H. Moncure Conway described Whistler’s approach to decoration in his Travels in South Kensington: with Notes on Decorative Art and Architecture in England (1882):

“Mr Whistler dots the walls and even the ceiling of his rooms with the brilliant Japanese fans which now constitute so large an element in the decoration of many beautiful rooms; but in his drawing-room there were fifteen large panels made of Japanese pictures, each about five feet by two. These pictures represent flowers of every hue, and birds of many varieties and of the richest plumage … There is also in the room an ancient Chinese cabinet with a small pagoda designed on the top, and old Japanese cabinet of quaint construction, and several screens from the same region, altogether making one of the most beautiful rooms imaginable.”

A letter from Sydney Morse, Whistler’s successor at No. 96, dated 1888, describes redecorating the interior of the house:

“We had agreed that Cossins should redistemper 96, Cheyne Walk in the scheme of colouring which Whistler decided for us. He was so afraid we should do it wrongly that he personally superintended the work and mixed the colour himself. In consequence of this a whole “wash” for the Dining room wall was spoilt as he forgot to stir it up at the right moment – there was great discussion about gold size. The hall had 2 fine panels in blue on white by Whistler, 2 ships with sails set at sea. The house was coloured as “a sunset.” The gold dado on the stairs was dotted with pink and white chrysanthemum petals. The drawing room we papered, also the studio, but not till Whistler had gone in Sept(embe)r.”

As well as being a rugby union international, Morse was also as a collector of art and owned works by Blake, Whistler and a number of Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood artists. William Holman Hunt also did a drawing of Sydney Morse himself, ca.1897–8.

In about 1908 Nos. 95 and 96 were combined as a single house with the ground floor of No. 95 arranged as the service wing to No. 96.

In 1921, Lord Ednam commissioned the architect Philip Tilden to extend the north-east wing to the west, providing a corridor on the ground floor and a large bay window with canted sides on the first floor. Tilden also inserted a large new staircase from the ground floor front room of No. 95 (the old Servants’ Hall), to the first floor, sealing the door from the new staircase compartment to the drawing room.

In the late 1930s, the ground floor of the building was occupied by the Royal Historical Society (RHS). In the 1950s the second and third floors were occupied as flats by separate leaseholders. At that time the RHS were still on the ground floor (and possibly also the first floor) By 1962 Gerald Hochschild, of the South American mining family, owned the house. He commissioned significant alterations and an extension from Philip Jebb, an architect who specialised in the renovation of Georgian buildings for society clients. In more recent years Paul Channon M.P. lived in the house.

I was asked to see if anything of Whistler’s mural decoration had survived under later paint. While in the house I was able to identify the room that he had used as his studio to paint the famous portraits of his mother and of Thomas Carlyle.

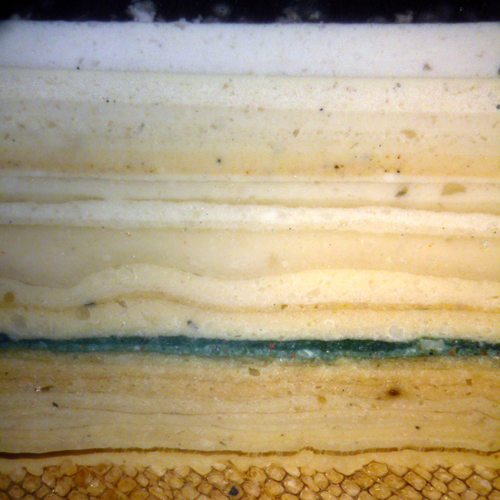

The portraits of Whistler’s mother and of Thomas Carlyle show a background of grey walls and a high black skirting (see painting above). When one looks at a cross section made from a sample from the skirting of one of the rear rooms a black scheme can be seen clearly. The estimated repainting cycle gives a date of ca.1870 for this. Once again paint analysis can often be the only tool to establish facts such as this.

NOTES

1 The two Rossettis being the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his brother William Michael Rossetti.

2 Giles Walkley. Artists’ Houses in London, 1764-1914 Scolar Press. 1994.

This has been taken from Wikipedia and a report produced by Alan Baxter & Associates on 95-96 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. July 2011.

The property was purchased in the 1930s by Bryan Guinness, I believe shortly after he divorced his first wife Diana (one of the Mitford sisters who went on to marry Oswold Mosley). Bryan Guinness sold 95/6 to my father, Richard Stewart-Jones, in about 1943. Richard – who already owned 94 next door – moved in his mother and two sisters who lived there in the early part of World War 2. I believe he sold a long lease to Peter Croyer in about 1950 and then gave the freehold of the building to the Royal Historical Society. Paul and Ingrid Channon bought 95/96 in the sixties and then bought the next door property, 94, in 1979 from my mother who had been widowed some years earlier. in 1956 Peter Croyer wrote a book about his house and the other houses stretching up to 100 Cheyne Walk:- “The Story of Lindsey House, Chelsea” .

Very many thanks Barney. All very interesting.

I’m writing a biography of Emilie Ashurst and her sisters, daughters of the man who founded the City law firm, Ashursts. Among other things, Emilie was a close friend of Mazzini, a portrait painter, and translator of Mazzini’s work. She twice lived at 95 Cheyenne Walk, first (as Mrs Emilie Hawkes) in 1§857, and later (having divorced Hawkes, re-married, and been widowed) as Madame Venturi, during 1875 and 1876. She also lived with her sister Caroline Stansfeld and her first husband nearby at Belle Vue Lodge (91 Cheyne Walk) from 1851 until Hawkes was declared bankrupt and decamped to Belgium with his mistress and their children. She figures in Whistler’s letters (as also in those of Swinburne, the Carlyles, Dickens, Mazzini, etc. I’m intrigued by the connecting doors between 95 and 96, which may now have gone. I see material on the net about reconfiguration in 2014 or thereabouts.

Thanks Charles. Yes, there were interconnecting doors, but I haven’t been in the building since 2012 and don’t know how it’s changed.