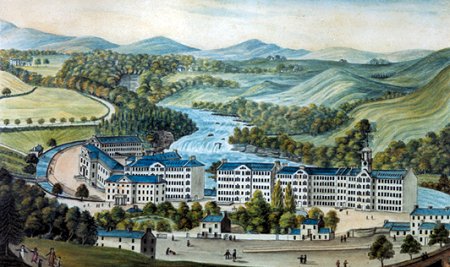

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 2.2 km from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some 40 km southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and housing for the mill workers. Dale built the mills there in a brief partnership with the English inventor and entrepreneur Richard Arkwright to take advantage of the water power provided by the only waterfalls on the River Clyde. Under the ownership of a partnership that included Dale’s son-in-law, Robert Owen, a Welsh philanthropist and social reformer, New Lanark became a successful business and an epitome of utopian socialism as well as an early example of a planned settlement and so an important milestone in the historical development of urban planning.

The New Lanark mills operated until 1968. After a period of decline, the New Lanark Conservation Trust (NLCT) was founded in 1974 (now known as the New Lanark Trust (NLT)) to prevent demolition of the village. By 2006 most of the buildings had been restored and the village has become a major tourist attraction. It is one of five UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Scotland and an Anchor Point of ERIH – The European Route of Industrial Heritage. The tenement which is the subject of my work here is designated a Scheduled Monument and is also an ‘A’ Listed Building, both an indication of the importance of the building’s survival as a rare heritage asset.

The New Lanark cotton mills were founded in 1786 by David Dale in a brief partnership with Richard Arkwright. Dale was one of the self-made ‘Burgher Gentry’ of Glasgow who, like most of these people, had a summer retreat, an estate at Rosebank, Cambuslang, not far from the Falls of Clyde, which have been painted by J.M.W. Turner and many other artists. The mills used the recently developed water-powered cotton spinning machinery invented by Richard Arkwright.

Dale sold the mills, lands and village in the early nineteenth century for £60,000, payable over 20 years, to a partnership that included his son-in-law Robert Owen. Owen, who became mill manager in 1800, was an industrialist who carried on his father-in-law’s philanthropic approach to industrial working and who subsequently became an influential social reformer. New Lanark, with its social and welfare programmes, epitomised his Utopian socialism (Owenism). The town and mills are important historically through their connection with Owen’s ideas, but also because of their role in the developing industrial revolution in the UK and their place in the history of urban planning.

The New Lanark mills depended upon water power. A dam was constructed on the Clyde above New Lanark and water was drawn off the river to power the mill machinery. The water first travelled through a tunnel, then through an open channel called the lade. It then went to a number of water wheels in each mill building. It was not until 1929 that the last waterwheel was replaced by a water turbine. Water power is still used in New Lanark. A new water turbine has been installed in Mill Number Three to provide electricity for the tourist areas of the village.

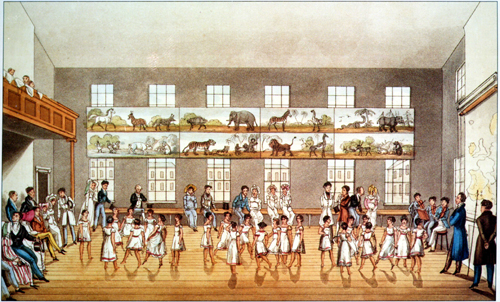

In Owen’s time some 2,500 people lived at New Lanark, many from the poorhouses of Glasgow and Edinburgh. Although not the grimmest of mills by far, Owen found the conditions unsatisfactory and resolved to improve the workers’ lot. He paid particular attention to the needs of the 500 or so children living in the village (one of the tenement blocks is named Nursery Buildings) and working at the mills, and opened the first infants’ school in Britain in 1817, although the previous year he had completed the Institute for the Formation of Character.

The mills thrived commercially, but Owen’s partners were unhappy at the extra expense incurred by his welfare programmes. Unwilling to allow the mills to revert to the old ways of operating, Owen bought out his partners. In 1813 the Board forced an auction, hoping to obtain the town and mills at a low price but Owen and a new board (including the economist Jeremy Bentham) that was sympathetic to his reforming ideas won out.

New Lanark became celebrated throughout Europe, with many leading royals, statesmen and reformers visiting the mills. They were astonished to find a clean, healthy industrial environment with a content, vibrant workforce and a prosperous, viable business venture all rolled into one. Owen’s philosophy was contrary to contemporary thinking, but he was able to demonstrate that it was not necessary for an industrial enterprise to treat its workers badly to be profitable. Owen was able to show visitors the village’s excellent housing and amenities, and the accounts showing the profitability of the mills.

As well as the mills’ connections with reform, socialism and welfare, they are also representative of the Industrial Revolution that occurred in Britain in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and which fundamentally altered the shape of the world. The planning of employment in the mills alongside housing for the workers and services such as a school also makes the settlement iconic in the development of urban planning in the United Kingdom.

As the years passed Robert Owen grew more disillusioned as his plans for model communities failed to make any progress. Even in New Lanark, an outstanding success in social reform,1 he was encountering problems with his business partners. His thoughts on religion and education clashed with theirs and his desire to channel funds into the social welfare of the villagers, against the will of his commercially focused partners, caused tensions.

In 1825, control of New Lanark passed to the Walker family when Owen left Britain to start settlement of New Harmony in Indiana, USA.2 The Walkers managed the village until 1881, when it was sold to Birkmyre and Sommerville and the Gourock Ropeworks (although they tried unsuccessfully to sell the mills and the town in 1851. They and their successor companies remained in control until the mills closed in 1968.

The town and the industrial activity had been in decline before then, but after the mills closed migration away from the village accelerated, and the buildings began to deteriorate. The top two floors of Mill Number One were removed in 1945 but the building has since been restored and is now the New Lanark Mill Hotel. In 1963 the New Lanark Association (NLA) was formed as a housing association and commenced the restoration of Caithness Row and Nursery Buildings. In 1970 the mills, other industrial buildings and the houses used by Dale and Owen were sold to Metal Extractions Limited, a scrap metal company. In 1974 the NLCT (now the NLT) was founded to prevent demolition of the village. A compulsory purchase order was used in 1983 to recover the mills and other buildings from Metal Extractions after a repairs notice had been served in 1979. This was because of the state of repair of the buildings despite their listing as historic buildings that required their legal preservation in 1971. They are now controlled by the NLT, either directly through the Trust or through wholly owned companies (New Lanark Trading Ltd, New Lanark Hotel Ltd and New Lanark Homes).

Living Conditions

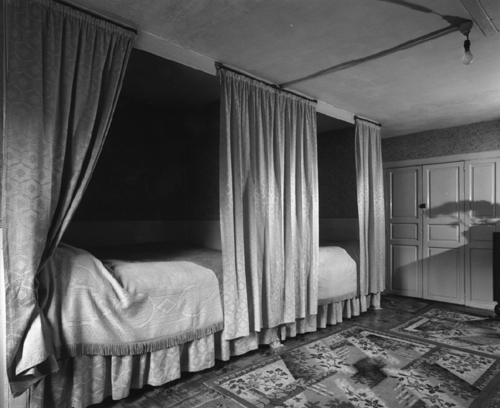

In the mid nineteenth century, an entire family would have been housed in a single room. The living conditions in the village gradually improved, and by the early twentieth century families would have had the use of several rooms. It was not until 1933 that the houses had interior cold water taps for sinks and the communal outside lavatories were replaced by inside facilities.

From 1938 the village proprietors provided free electricity to all the homes in New Lanark, but only enough power was available for one dim bulb in each room. The power was switched off at 10pm Sunday-Friday, 11pm Saturday. In 1955 New Lanark was connected to the National Grid. In the 1960s it is known that five or six families were still resident in the tenement although the top floor had been abandoned by that stage. The last occupant was Elizabeth Jess who lived on Floor Two until 1972.

Today

It has been estimated that over 400,000 people visit the village each year. The importance of New Lanark has been recognised by UNESCO as one of Scotland’s five World Heritage Sites, the others being Edinburgh Old and New Towns, Heart of Neolithic Orkney, St Kilda and the Antonine Wall. The mills and town were listed in 2001 after an earlier unsuccessful application for World Heritage listing in 1986.

About 200 people live in New Lanark. Of the residential buildings, only Mantilla Row and Double Row have not been restored. Some of the restoration work was undertaken by the NLA and the NLCT. Braxfield Row and most of Long Row were restored by private individuals who bought the houses as derelict shells and restored them as private houses. In addition to the 20 owner-occupied properties in the village there are 45 rented properties let by the NLA, which is a registered housing association. The NLA also owns other buildings in the village.

In 2009 the NLA was wound up as being financially and administratively unviable, and responsibility for the village’s tenanted properties passed to the NLCT.

Considerable attention has been given to maintaining the historical authenticity of the village. No television aerials or satellite dishes are allowed in the village, and services such as telephone, television and electricity are delivered though buried cables. To provide a consistent appearance all external woodwork is painted white, and doors and windows follow a uniform design. Householders used to be banned from owning dogs, but this rule is no longer enforced.

The mills, the hotel and most of the non-residential buildings in the village are owned and operated by the NLT through wholly owned companies.

The House

109-119 Rosedale Street was built ca.1795. It is one of 8 terraced buildings on the south west side of the street that was formerly known as Double Row and is the second building from the furthest west. It is a five storey tenement block, containing back-to-back apartments and an attic floor. The side facing the river was also known as Water Row. Most floors have either four or five rooms. The basement became a laundry room in later years.

I was asked to carry out an analysis of the decorative finishes in all the rooms that comprise the tenement. It was possible to learn a great deal of their decorative history.

NOTES

This has been taken from Wikipedia with a number of amendments and additions. The Conservation Plan written by Mrs Gille Young has also been an excellent source of information. Another very useful source has been New Lanark and Efficiency Wages. Economics of the New Lanark Establishment under Robert Owen’s Management (1800-1825) by Monojit Chatterji of the University of Dundee.

1 Perhaps one shouldn’t view this through rose-tinted spectacles. It appears that the changes made at New Lanark took place without consulting those who would be affected most by them i.e. the workers. Owen’s “humanitarian” intentions were aimed at what he labelled his “human engines”, who were compelled to adopt whatever measures Owen believed necessary for the creation of a happy and efficient workforce. Other mill owners were also known to have cared for their workers although few received as much credit and fame as Owen.

2 That project also failed as its members were a motley collection, mixing many worthy people of the highest aims with vagrants, adventurers, and crotchety, wrongheaded enthusiasts, or in the words of Owen’s son “a heterogeneous collection of radicals, enthusiastic devotees to principle, honest latitudinarians, and lazy theorists, with a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in.” Other Owenite communities appeared in the USA between 1825 and 1829, however none lasted more than a few years as communities.

Great piece, thanks! You may be interested in this: http://bit.ly/1JCp99e

Very many thanks for that.

It’s amazing place. When I look on those pictures, I think that I would like to go back in time and see how life was once …

Thank you for this post. I will back here