On two occasions so far I have been asked to work on houses with strong connections with my family. The first time was a charming Regency house in Essex, where I had spent many of my early summers. On this latest occasion it was a house that my grandmother’s family had lived in throughout the nineteenth century. Long out of family ownership, but still in our collective memory.

Trent Park is situated in the very heart of Enfield Chase, and sits in 413 acres of rolling meadows and ancient woodland. It forms part of London’s Green Belt and being a country park it provides a tranquil rural environment right on the outskirts of London.

After the Norman invasion of 1066, the huge forest known as Enfield Wood, passed to Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex, and his descendants. It was in 1136 that one of these converted the area into a hunting park and stocked it with fallow deer. This passed by marriage to the de Bohuns, Earls of Hereford, and then by marriage again into Royal ownership. From 1421, Enfield Chase was administered by the Duchy of Lancaster.

In 1777 George III gave his consent to an Act of Parliament1 to divide, enclose and disafforest the 8,349 acres that made up the royal hunting forest of Enfield Chase.2 The land was divided and sold in lots, with two lots earmarked as a miniature hunting park. The lease of this area was granted in 1779 to Sir Richard Jebb, his physician, who built a villa called Trent Place. This had been named after the Italian town where he had cured the King’s younger brother, the then Duke of Gloucester, of a serious illness.

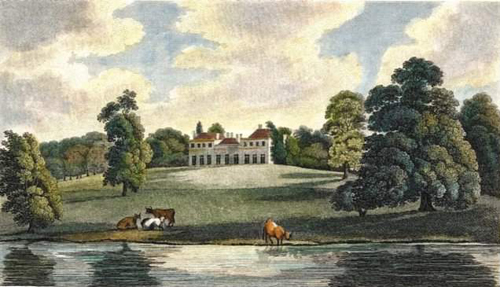

The first Trent Place was a ‘compact villa’ of brick, with a portico and a curved central portion.3 It is known that Sir William Chambers carried out unspecified alterations for Jebb and Humphry Repton was said to have beautified the house and its grounds, which contained a lake, for John Cumming, the occupier in 1816. A drawing in Enfield Local Studies Library & Archives shows the house at about this time (see below).

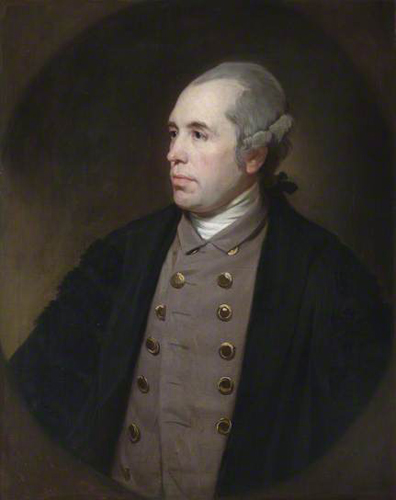

After passing through several hands, in 1833 a 99 year lease was bought by David Bevan, of Belmont, in nearby East Barnet. He was a Quaker,4 one of a long line of the banking family and a partner in the London bank of Barclay, Bevan & Co (which would become Barclays).

A (probably apocryphal) family story suggests that David nodded off at an auction and woke to find himself the owner, a nod being taken as a bid. However, we do know that he paid £25.586 for it – £18,000 for the house and park and £7,586 for the timber.

In 1837 David assigned the lease to his son Robert Cooper Lee Bevan, who had followed his father into the bank. Robert and his wife made their permanent home at Trent Park (having changed the name from Trent Place), varied by occasional visits to their country house at Fosbury, in Wiltshire and Collingwood House, Brighton.

David Bevan died in a tragic fire at Belmont in 1846, aged seventy-two and was buried in the Bevan family tomb at Christ Church, Cockfosters, which was built by his son Robert in 1838. Many other Bevans are buried in the tomb and are also recorded in the stained glass windows.

It was during Robert’s time that a number of additions were made to the house, including a tower on the east side.5 Further landscaping was carried out, including the mass planting of oak trees and the double avenue of lime trees planted along the main drive. In 1857 the Trent Park estate consisted of 475 acres, while Robert leased another 93 acres, called Clay Pit Hill farm to the north-west, and 114 acres at Cockfosters to the south.

Life during Robert Bevan’s time at Trent was described by a member of the family as ‘austere’.6 There was only one bathroom, no billiard or smoking room and no electric light, and social life was almost non-existent apart from prayer meetings and other religious gatherings.7

On account of his health the London house, 25 Prince’s Gate, was sold and the Villa, Châlet Passiflora, bought at Cannes, where Robert spent the winters, returning to Trent and Fosbury for the summer months.8

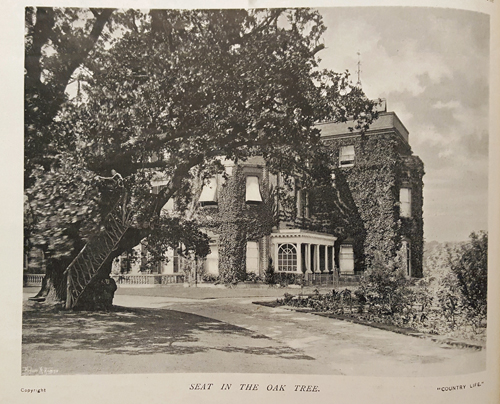

Robert Bevan died in July 1890 and was buried in the family tomb at Trent Church. The estate passed to his eldest son, Francis Augustus, who obtained a £10,000 grant from the Duchy of Lancaster to modernise the mansion.9 He transformed it from an Italian-style villa to the reddish-mauve brick pile which a sister of his compared to a railway hotel.10

The anonymous author of a Country Life article, of 1903, very tactfully skipped over the house, merely describing it as ‘a large red-brick pile, creeper-clad, and bowered in woodland.’ However, he did say that ‘Within the walls are many highly interesting objets d’art, chief of which may be mentioned some specimens of Beauvais tapestry in excellent preservation. The pictures include examples of the art of Gainsborough, Turner, Daubigny, Linnell, Frère, Morland, Zucchero,11 Constable, and many other famous painters.’

The Victorian house was not a pretty building but, as Christopher Hussey wrote,

It would be difficult to find a more perfect setting for a country house…12

The location was also perfect for the Bevans to get to the headquarters of the bank at 54 Lombard Street, only fourteen miles from the house.

Francis also bought 57 acres south of the main estate from the Duchy of Lancaster in 1892 and made great improvements to the gardens. The long rose walk is said to have had 238 different varieties.

In the summer, tea could be taken in the Tree House, in a massive oak tree complete with its own staircase, while overlooking the rhododendrons and chrysanthemums for which the garden was renowned.

However, in exchange for the grant, the Duchy of Lancaster increased the rent and Francis Bevan was beginning to find the house too large for his needs. His wife and youngest son had died and his other children had married and moved away. So, in 1909 he sold the remaining 26 years of the lease for £12,114 to Sir Edward Sassoon and settled into a house at No 1 Tilney Street, Mayfair.

Trent Park was soon to enter its most interesting phase and this is covered in part two.

Camlet Moat13

Within the grounds of Trent Park, 900m to the north of the house, is a medieval water-filled moated site, traditionally known as Camlet Moat.

The moat is quadrangular in shape and orientated NNE to SSW. The island in the middle is about 69m long by 53m wide with rounded corners. The moat is on average about 10m wide, varying from 5m wide at the narrowest point to 15m wide at the corners. On the eastern side is a causeway giving access to the island, which stands up to about 2m above the level of the water in the moat.

All kinds of theories have been put forward about the purpose of the building that once stood on the island. It may have been a Mandeville house; or the quarters for the Head Forester of Enfield Chase, or indeed, a hunting lodge. In the late 1880s Nesta, one of Robert Bevan’s daughters, helped her mother and a number of the estate workers excavate some of the site. In her autobiography she describes uncovering ‘a whole dungeon with a chain attached to the wall’; timber from the drawbridge as well as roof tiles, silver coins of Edward IV (1470-83), a lady’s thimble and glazed tiles. It is not known where these objects are now.14

A subsequent excavation carried out by Sir Philip Sassoon in 1923 found more timbers from the drawbridge, which was calculated to have been quite impressive in size. Over 22m of the walls of the early building were found about 1.5m below the surface.

In 1997, English Heritage carried out desilting work in the moat and found even more of the drawbridge. Dendrochronological testing revealed a felling date of sometime after 1357, which may tie in with Humphrey de Bohun’s 1347 licence to crenellate his manor houses.

The moat at Camlet has attracted more than usual interest for a number of reasons. Sir Walter Scott mentions it in The Fortunes of Nigel. The name Camlet is said to derive from “Camelot”, with implied Arthurian associations, and the moat is also said by some to be haunted by the ghost of the twelfth century knight Geoffrey de Mandeville.

In 1440, a house called ‘the manor of Camelot’ was apparently demolished and the materials used to pay for repairs to Hertford Castle. In 1773, the site is described as ‘the ruins and rubbish of an ancient house’. Later sources also refer to a well situated in the north-east corner with a paved bottom.

Under this pavement, so goes the story, is buried a great chest of gold and precious stones that no one is able to carry up because it is bound to the place by a spell of enchantment.15

Sadly, to date, no funding has been made available to launch a serious archaeological excavation.

NOTES AND SOURCES OF INFORMATION

1 (17 Geo. III, c. 17.)

2 Parks & Gardens UK.

3 British History Online.

4 As they prospered, intermarried and mixed with evangelical philanthropists and business men the Bevans soon ceased to belong to the Society of Friends. However, they retained a Quaker capacity for hard work and singlemindedness. (John S. Andrews. The Recent History of the Bevan Family. The Evangelical Quarterly. April – June 1961. 81-92).

5 This was described as being ‘of peculiarly hideous appearance’ by Christopher Hussey in Country Life (January 10th 1931 p.43).

6 Manuscript document in the possession of the family.

7 Robert had been a keen horseman and huntsman. As a young man he had ridden down ‘The Devil’s Dyke’ near Brighton, a dangerous feat only once previously accomplished by a man called ‘Mad Wyndham’. However, at the age of twenty-seven he became an Evangelical Christian and gave up hunting. Together with his friend, Lord Shaftesbury, he sought to better the conditions of the working classes. He was one of the founders of the London City Mission. Lady Agneta (née Yorke), his first wife died in 1851 and five years later Robert married Emma Frances Shuttleworth, daughter of the Bishop of Chichester. She was the author of several religious works and a translation of the hymns of Gerhard Tersteegen. (John S. Andrews. Frances Bevan: Translator of German Hymns. The Evangelical Quarterly. January – March 1963. 30-38).

8 Audrey Nona Gamble (née Bevan). A History of the Bevan Family. 1923, 127.

9 See this essay on Robert Bevan’s wealth and family.

10 Manuscript document in the possession of the family.

11 Possibly Taddeo Zuccari.

12 Country Life. January 10th 1931. p.42.

13 A very good account of the house and of Camlet Moat can be seen in this PDF: Alan Mitellas. A Concise History of Trent Country Park. June 2015.

14 Nesta Webster (née Bevan). Spacious Days: An Autobiography. 1950. One wonders if anyone has asked the descendants of Robert Bevan about these items.

15 Country Life, February 21st 1903. p.243-44.

No comments yet. Be the first!