The King’s Observatory was an astronomical and terrestrial magnetic observatory built for George III, a keen amateur astronomer. The architect was Sir William Chambers who also designed the Pagoda in nearby Kew Gardens. It is located within the Old Deer Park of the former Richmond Palace in Richmond, Surrey. The Observatory grounds overlie to the south the site of a former Carthusian Priory which was established by King Henry V in 1414 and which was eventually demolished when the building of the observatory began. It is built of Portland stone and designed as a villa with a moveable dome observatory mounted on the top. The building is in its original design state apart from the raising of the side roofs to the level of the observing dome, which happened in 1888 (East) and 1892 (West).

The main telescopes were in the movable dome which had an opening roof. The west of the observatory was used for the day to day transit observations. The room on the east side was used for quadrant observations. There are three obelisks built in 1769 of Portland stone to aid the alignment of the instruments. One is positioned to the North of the centre of the observatory. The two others mark south from the transit and quadrant rooms.

© Copyright Nigel Chadwick and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

The Observatory was completed in time for the King to watch the transit of Venus (i.e. when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and the Earth) on June 3rd 1769.

The Observatory was used as an educational centre by the princes and the King established his own workshop there. The first Royal Observer to be appointed was Dr Stephen Demainbray, who held the post from 1769 to 1782. He was assisted by his son the Rev. Stephen Demainbray who became teacher of astronomy to the King’s children.

In 1795 John Little, who was at one time a curator at the Observatory, was hanged for the murder of two old people in Richmond, and was also suspected of having caused the death of a man named Stroud, whose body was found under an iron vice in the octagon room of the building. This man, Little, had often been George III’s only attendant when he walked in the gardens.3

At one time, London’s official time was set from the calculations made at Kew. The principal time-piece used was made by Benjamin Vulliamy, clock-maker to the King. Later this work was taken over by the Observatory at Greenwich.

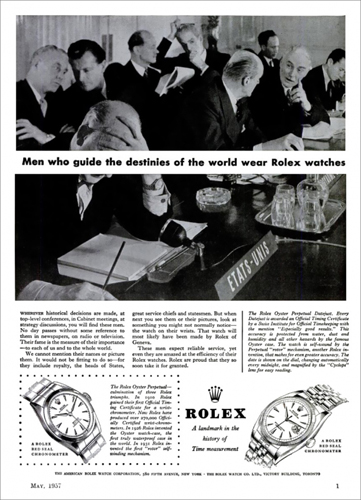

Kew also played a role in testing timepieces for accuracy, based on stringent standards aligned with measurements of the stars. As marine navigation adopted the usage of mechanical timepieces for navigational aid, the accuracy of such timepieces became more critical. The testing process lasted for many days, typically 45 days. Each movement was tested in 5 positions and 2 temperatures, in 10 series of 4 or 5 days each. This work, along with observatories in Neuchâtel and Geneva in Switzerland and Besançon in France, gave rise to the Observatory Chronometer mark of quality for timepieces, which remained predominant until the advent of quartz timekeeping in the late 1960s. Other instruments was also sent to Kew for comparison or calibration – initially just thermometers, but later barometers, binoculars and watches were also tested. The ‘KO’ mark, which was introduced in 1878 to brand instruments which had been tested and approved at the Kew Observatory became an internationally recognised guarantee of accuracy.

The Institution remained royal property until 1840. In 1841 it was closed and much of the contents, including George III’s collections of instruments and Queen Charlotte’s natural history collection, were removed from the building and dispersed to various places. These had been housed in the glass-fronted cabinets which line the main rooms.

Dr John Evans in his Richmond and its Vicinity (1824) describes the collections as ‘some excellent mathematical instruments, a collection of subjects in natural history, well preserved, an excellent apparatus for philosophical experiments, and a collection of ores from His Majesty’s mines in the forests in Germany’. An article by R. S Whipple on ‘An old Catalogue and the Scientific Instruments and Curios of George III’ published in The Proceedings of the Optical Convention 1926 describes the collections in detail, and a splendid book by Alan Morton and Jane Wess, entitled Public and Private Science: The King George III Collection was published by the Oxford University Press, jointly with the Science Museum, in 1993 illustrating the items of the scientific collection. The Science Museum also published at the same time an illustrated booklet by Alan Morton Science in the 18th Century.2

The collection was dispersed in 1840 to the British Museum, King’s College, London and the Royal College of Surgeons and to various members of the Royal Family. Many of the instruments are now in the Science Museum and the National Maritime Museum.

The British Association for the Advancement of Science took over the Observatory in 1842.

In 1867 the Observatory became the central observation station for the newly established Meteorological Office. Finding it too much of a burden the British Association handed over management of the building to the Royal Society in 1871. In 1900 the newly-established National Physical Laboratory took over the management until the Meteorological Office assumed control from July 1910.

Finally, in 1981, the building was offered on the open market on a Crown lease. It was restored by The Lesser Group and a head lease sold to Hill Samuel Bank who sub let it to Solaglas. That lease has recently expired.

I was asked to examine the paint on the magnificent cabinets that line the walls of the main rooms on the ground and first floors. I have since been appointed to guide the redecoration of the interior.

A website outlining the restoration of this building can be found here.

1 Not to be confused with this Transit of Venus – courtesy of Dr Jonathan Foyle, Chief Executive of World Monuments Fund Britain.

2 Taken from John Cloake’s report: The King’s Observatory, Old Deer Park, Richmond, which I have heavily relied on for this post.

3 Taken from Local History Notes produced by the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.

View Larger Map

Simultaneously quite plain yet handsome and well-proportioned as is the Georgian Way. Utilitarian.