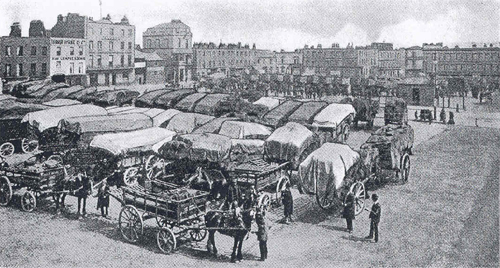

Messrs. J. & A. Crew occupied the left hand of the two tall buildings

“It is not near Piccadilly: it is a place of carts and the sky. Cabs and trains know nothing of it, and on the map you will find it very small, though it is more important than Piccadilly; it is in the real world…

…there is a horse-trough in the centre, cutting one of the two lines of black posts marking the road off from the great stretch of cobble-stones on either side; and one clean house with a pediment freshly painted, from which the pigeons fly. And there is the British Queen at one corner looking crossways at the King’s Head at the other, and opposite the British Queen the Jolly Farmers…

The carts are always there: the hay-stacked carts with the empty shafts, standing like exiled ricks in a vast, strange yard; and the big two- or four-horsed drays loaded with coal sacks, meal sacks, beer casks; half asleep, pulling up mechanically at the horse-trough and the Jolly Farmers…”2

Charlotte Mew was describing a part of London that finally disappeared over fifty years ago, having been in steady decline since the early years of the twentieth century.

Cumberland Market clearly represented the “real world” to Robert Bevan and his fellow Neo-Realists Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner. It was there, in the months before the First World War, that Bevan took a studio and formed what was to be a short-lived successor to the Camden Town Group.

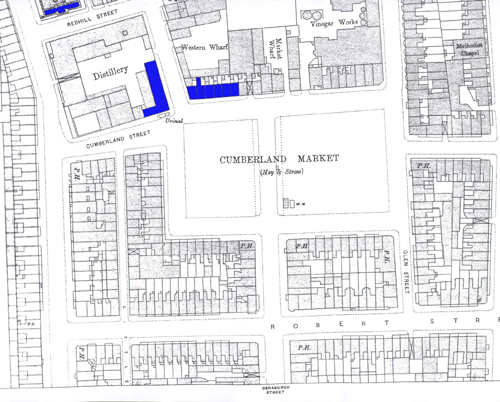

The land to the east of John Nash’s Regent’s Park development had originally been laid out as a service district with small houses for tradesmen and three large squares intended for the marketing of hay, vegetables and meat.3 Only Cumberland Market, the northernmost square survived as a commercial area. London’s hay market relocated here from Piccadilly in 1830 although it was never to prove a great success, being described in 1878 as “never [having] been very largely attended”.4

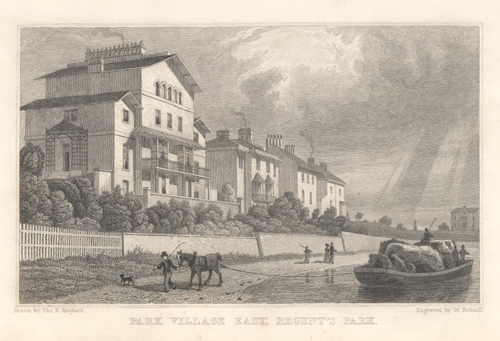

The Regent’s Canal was developed as a means of delivering goods into the North of London. It linked the Grand Junction Canal’s Paddington Arm with the Thames at Limehouse.5 The Cumberland Arm was built as a spur off it and led between Nash’s Park Village West and Park Village East to the Cumberland Basin which was lined by a collection of wharfs and warehouses. Hay and straw were brought in for sale at the Market and for the nearby Albany Street cavalry barracks.6 Barges, each capable of carrying thirty tons, would also arrive with heavy goods such as stone and lime for building; coal and timber for the neighbouring coach-building and furniture trade. Ice, too, was brought in for the ice-merchant, William Leftwich, who had an icehouse that was eighty-two feet deep and with a capacity of 1,500 tons under the Market.7 Vegetables and cattle were carried in as well, thus reducing the need for the latter to be driven into the city.

Clarence Market, the next square to the south, was intended to be a centre for the distribution of fresh vegetables brought in from the market gardens of Middlesex. It was later cultivated as a nursery garden and became Clarence Gardens.8 The houses in Clarence and Cumberland Markets were modest and the work of speculative builders who put up “run-of-the-mill products without the slightest obligation to make architecture.”9 The southernmost square began as York Market but it never found use as a trading place and the name was later changed to Munster Square. Although its houses were tiny, with a single window on each of their three storeys, they were well-designed and perfectly proportioned.10

“I saw [Munster Square] in the Blitz, and in the black-out: in rain and snow, in sunshine and in the shade of street-lighting. Maybe it is not an architectural jewel . . . but I loved its square entity, the harmony of its small fronts, the delicate ironwork of its balconies . . . and it gives the peculiar feeling of an immense room, with the skies as the roof: the same feeling you have in evenings on the Piazza San Marco in Venice: a ballroom.”11

In the NW corner of Cumberland Market, in Albany Street, John Nash had built the Ophthalmic Hospital for Sir William Adams, George IV’s oculist. For several years Adams gave his services free to soldiers whose eyesight had been affected in the military campaigns in Egypt. The hospital was closed in 1822 and for a time it was used as a factory for manufacturing Bacon’s and Perkin’s ‘steam guns’. In 1826 it was purchased by Sir Goldsworthy Gurney for the construction of his famed ‘steam carriages’, one of which made the journey from London to Bath and back, in July 1829. However, unable to market these vehicles Gurney was forced to sell the premises in 1832. Bought by Sir Felix Booth, the gin distiller the building survived as a landmark, although badly bombed, until demolition in 1968.

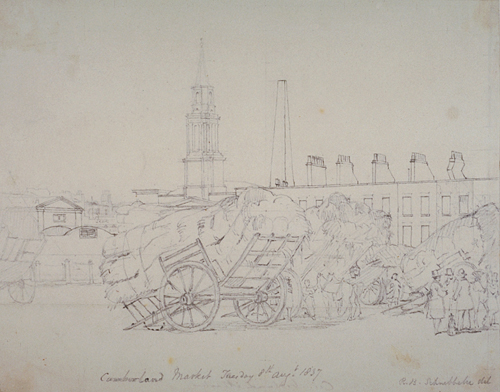

Reproduced with the permission of the Guildhall Library, City of London

Beside the Ophthalmic Hospital was Christ Church, built by Nash’s assistant, Sir James Pennethorne in 1837 to serve the largely working class district.12 However, a series of later alterations gradually made the church more appropriate for high-church worship, and in time the windows were filled with stained glass, including a panel by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose family worshipped there.13

The steeple of Christ Church dominated Cumberland Market as did the nearby chimney of William Grimble’s gin distillery, also in Albany Street. In 1840 Grimble decided to embark on producing vinegar from spirit left over from his distillery. He went into partnership with Sir Felix Booth, and they set up premises in the North East corner of the Market. The venture was unsuccessful so they turned to the more conventional method of vinegar brewing. The brewery burnt down in 1864 and was rebuilt and extended soon after.14

The growth of the railway network and the opening of Euston Station in 1837 caused enormous upheaval and was one of the factors that led to the rapid decline of the area. Bringing in “noise, dirt, Irish navvies, and semi-itinerant railway workers”15 Charles Dickens likened the railway works cutting their way through Camden Town to a “great earthquake”.16 More industry developed in the area than was originally planned as factories began to spring up near the canal and railway and this put even more pressure on land for housing. Houses that were originally built for middle class families were taken over by incomers. The terraces of Mornington Crescent and Arlington Road, for example, were ideal for multi occupation for as many as nine or ten people could be accommodated in each.17

From an original study by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (1793-1864), pub 1831. Produced from Shepherd’s series Metropolitan Improvements; or London in the Nineteenth Century.

This view is looking south towards Cumberland Market

By 1852 the Midland Railway was transporting around a fifth of the total coal to London through Euston and King’s Cross.18 Although still in use the Regent’s Park Canal carried less and less until by the 1850s the Cumberland Basin was described as “no better than a stagnant putrid ditch”.19 Cholera spread through the families of men who were employed on the barges and in the wharves around it and took hold in the overcrowded neighbourhood.

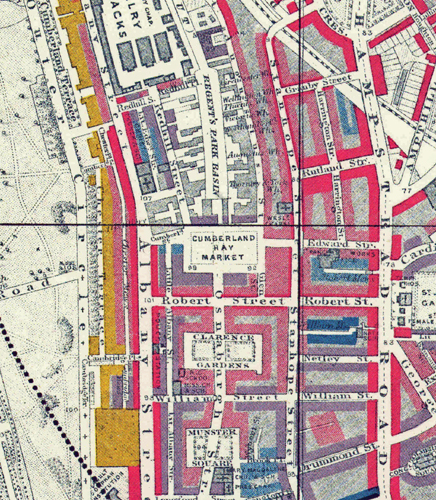

The housing situation was to become worse in the following decade. Some 4,000 houses were demolished in the area to the east of Cumberland Market to make way for the new St Pancras Station in 1868. As many as 32,000 people were displaced, most with no form of compensation.20 By the late nineteenth century a dramatic social divide had developed in this part of London with Cumberland Market in the middle. Just over one hundred metres to the west were the wealthy occupants of Nash’s Chester Terrace while a short distance to the east were areas characterised by Charles Booth, the social commentator, as being occupied by the very poor, of those in “chronic want”.

Part Two can be found here

Notes

1This appeared in the catalogue of an exhibition entitled A Countryman in Town: Robert Bevan and the Cumberland Market Group, which was held at Southampton City Art Gallery, September 26 – December 14, 2008. The title “Straws from Cumberland Market” refers to the title of an article by Walter Sickert in Art News 20th January 1910. Sickert also delivered a lecture with this title in Edinburgh in January 1923 and later in 1924 in Hanley, London, Manchester and Southport (Anna Gruetzner Robins. Walter Sickert. The Complete Writings on Art. Oxford 2000. 189-190.

2“The Hay-Market.” The New Statesman 14 February 1914. 595-597. Not that they knew it, but Charlotte Mew and Robert Bevan were cousins.

3Ann Saunders. Regent’s Park. A Study of the Development of the Area from 1086 to the Present Day. David & Charles. 1969. 83.

4Edward Walford. Old and New London. 1878. 299.

5Malcolm Holmes. Euston & Regent’s Park 1870. Old Ordnance Survey Maps. Sheet 49. Consett. Alan Godfrey. 2000.

6The canal was also used to take away manure.

7This was replaced by a ship constantly engaged in bringing ice from Norway to the Thames, where it was transferred to Regent’s Canal barges. This was eventually filled in with clay from the work on the Cockfosters underground railway extension in the early 1930s.

8John Summerson. Georgian London. Pleiades Books. 1945. 167. Clarence Gardens was the subject of a painting made by William Ratcliffe, a fellow Camden Town artist, in 1912. It is now in the collection of Tate Britain.

9John Summerson. The Life and Works of John Nash Architect. George Allen & Unwin. 1980. 128.

10See photograph of 1936 in Michael Mansbridge. John Nash. A Complete Catalogue. Phaidon. 1991. 183.

11Written 19th June, 1946, by Capt. S. Reychan to Mr. John Summerson and quoted in ‘Munster Square’, Survey of London: The parish of St Pancras part 3: Tottenham Court Road & neighbourhood. Volume 21. 1949. 139.

12The church was built in a severe Greek Revival style and is now St.George’s Greek Orthodox Cathedral. George Orwell’s funeral was held here in 1950.

13Geoffrey Tyack. Sir James Pennethorne and the making of Victorian London. Cambridge University Press. 1992. 35-36.

14See this link.

15Matthew Sturgis. Walter Sickert. A Life. Harper Collins. 2005. 221.

16Charles Dickens. Dombey and Son. 1848. Chapter 6.

17John Yeates. NW1. The Camden Town Artists. Heale Gallery. 2007. 8.

18See this link. Ironically the canal proved useful in the construction of both King’s Cross and St Pancras in terms of getting the building materials to the site.

19‘The Cholera’. The Medical Times and Gazette. New Series, Volume Seven. July 2 to December 31 1853. 429. In 1847 Pickfords transferred their entire freight business from the canals to the railways.

20(Survey of London 1949, 143).

View Larger Map

No comments yet. Be the first!